Today, the woodcarving of the Zafimaniry, Sakalava and Mahafale is the best known and most widely visible of Madagascar’s traditions, both inside and outside of the island. But, before 1950, connoisseurs admired as well another type: the carved wooden bed panels of the Merina1. Since that time, these panels have been largely lost from view2.

The modest objective of this article is to renew interest in historic Merina carving, and revisit earlier speculations concerning the inspiration for their intriguing iconography. In this, we rely heavily on the objects themselves. The recent initiative of museums worldwide to place their collections online allows scholars unprecedented access to the pieces themselves. But the nineteenth-century written record remains largely silent on the boards: who made or used them, and what their motifs represented or signified. We therefore caution against prematurely dating pieces, identifying motifs, or ascribing them meaning. What can be safely said is the carved bed panel flowered in the nineteenth-century, tied to rapid changes in domestic interiors and furnishings, to changing markers of status, and to a general shift toward realism in Malagasy arts.

The widespread wood carving traditions of Madagascar and changing academic fashions

Although today associated with only select peoples of the island, woodcarving in the past was widespread in Madagascar3. Shaping wooden objects formed part of men’s work, and objects of daily life were often artfully incised. The Betsileo, for instance, were observed to “carve geometric designs which are quite decorative not only on their funerary stelae, but also on the central posts of their homes, on the windows, shutters, bed boards, honey jars, water jar stands, handles of spoons, calabash and tobacco boxes”4. Elsewhere, men might additionally carve designs on wooden shelves, hair combs, mortars, lamp stands, shields, canes, headrests, coffins, wooden plates, weaving tools, trays and beds5.

In addition to the utilitarian, decorative, and geometric, Malagasy men sculpted three-dimensional objects associated with ancestral rites and healing, notably talismans (ody, aoly) and funerary art. The Sihanaka, Bara, Betsileo, Tanosy, Tandroy, Sakalava and Mahafale all historically had traditions of carving large wooden cenotaphs or tomb art, often in anthropo or zoomorphic forms. Sakalava and Mahafale funerary carvings are today the mostly widely known and praised. This in no small part relates to the “primitivist” aesthetic that emerged in the West from the 1910s. Attempting to break with western academic art and society, European avant-garde artists looked to nonwestern arts for inspiration, usually seeking out what they thought to be the most removed from the West, and the most spiritually powerful. Not coincidentally, it is a Sakalava funerary sculpture, formerly owned by the avant-garde British sculptor Jacob Epstein, that was chosen to represent Madagascar at the Louvre in 20046.

By the early 1920s, members of the French intelligentsia resident in Madagascar were aware of the metropole’s growing fascination with “l’art nègre”7. Yet they retained a wider appreciation of woodcarving. Indeed some authors considered Sakalava sculpture to be rather crude, and relatively recent8. They praised instead Merina carved bed panels as a more “ancient” tradition and the pinnacle of the Malagasy woodcarver’s skill. What were these panels, and why would they elicit admiration?

Beds and status

Historically, in most areas of Madagascar, people did not use bedsteads. As a missionary observed in the 1860s “a Malagasy does not think a separate room at all indispensable for a sleeping apartment; nor is a bed, in our sense of the word, an absolute requisite for his comfort. With a thin mat of straw he lies down contentedly on a hard floor”9. This observation held true for Imerina in the first quarter of the nineteenth-century: “In general, a coarse and strong matting, spread on the earth, constitutes the bed, table, and floor of the inhabitants”10. To this day, sleeping on the floor remains the practice for many in the island.

Nineteenth-century sources tell us that beds were rare on the coast, and more common in Imerina, Betsileo and Sihanaka territories, a fact which some attributed to the cooler climate of the central highlands: a bed provided elevation from the damp ground and freed space for keeping livestock or storing goods11. Into the mid nineteenth-century, houses in the central highlands (as throughout the island) consisted in a single rectangular room, thus making the bed (where used) a major focal point of the house interior.

The early Malagasy bed seems to have taken a number of shapes and styles. Amongst the Betsileo, it could be a closed cubicle:

The bedstead is generally made of wood reaching from the ceiling to the floor, and paneled all round, except a small opening, very like the door of the house, through which the occupant creeps when he enters or rises”12. Amongst the Sihanaka, some houses contained a “high bedstead consisting of some rush mats laid on cross-pieces of wood supported by four poles raised five or six feet above ground13.

Early sources on the Merina reveal only that it was large, square, “turned from dark wood” and “fixed in the northeast corner [of the house]”14. Ellis15 explained that the bedstead was “a fixture, the parts being driven into the ground”. More research is necessary, but early descriptions of Merina beds as fixed structures in house corners suggest that originally they were not discrete furniture, but were instead an extension of house wall construction, a sort of shelf. In fact, linguistic evidence from across the island points to the bed having perhaps originated as part of the shelves used for storing goods: early terms for the bed (kibany, farafara, kitrele) are synonyms for shelves, or platforms, generally something flat and raised16.

But bedsteads were more than utilitarian objects, or a matter of luxury or comfort. Instead, beds materialized notions of rank and status and their cosmological underpinnings, reserved for elders, nobles, and rulers. As numerous studies have shown, the binary opposition of up/down is key to conceptualizing and performing hierarchy in Madagascar. Superiors (ancestors, kings, elders, men …) physically place themselves above their subordinates. The bed was a means to this end. Its stature was increased by its placement: in Imerina, the bed was placed in the northeast corner of the house, the most sacred space. Associated with mystical strength and the ancestors, the northeast corner was reserved for storing talisman (sampy) and ancestral possessions and as the seating area for male elders17. The combination of height and orientation made the bed a prime manifestation of authority. It was allowed only to the eldest couple (e.g. grandparent) in the household, to nobles and rulers. Indeed, a bed’s height was commensurate with the owner’s social and political standing, the tallest beds being accorded to sovereigns18. James Sibree19 described a royal house in Ambohidratrimo as follows:

The roof is supported by three enormous posts, fifty or sixty feet high to the ridge, and nearly two feet in diameter. At one corner of the house is a square platform raised by posts ten or twelve feet above the ground. We were informed that this strange structure was the bedstead of the chief formerly the lord of the town and the surrounding country. Wondering how he managed to get into bed, we were pointed to one of the posts supporting the platform, which was notched at the angles. This served as a ladder for ascending to this couch20.

The beds in Andrianampoinimerina’s palaces at Ambohimanga (Mahandrihono) and Antananarivo (Besakana and Mahitsielafanjaka) conform to this description, although Jully21 records the bed in the last palace was located just 2.5 meters from the ground. Quite possibly it was carved with geometric designs (ibid.)22. However, it appears that into the end of the eighteenth-century, spatial considerations, rather than decoration, spoke the status of the bed owner. This would change in the early nineteenth-century, with the introduction of new signs of wealth, status, artisanal skills and iconography.

Merina bed boards (bois de lit)

In the study of Merina bois de lit, we dispose of four types of sources:

1- a few oblique contemporary passages from the nineteenth-century.

2- early short notices by Camo (1923), Camboué (1928), Fontoynont (1931)23, Waterlot (1931)24 and Boudry (1933)25. Subsequent works generally took the bulk of their information from Camo, Fontoynont and Waterlot.

3- illustrations in Camboué (1928), Boudry (1933), Fontoynont (1931) and the catalogue of a 1960 exhibition in Antananarivo, “Madagasikara. Regards vers le passé” (likey authored in large part by Charles Poirier). Fontoynont’s work includes the greatest number, 18 pieces from his private collection.

4- specimens and rubbings in museum collections: the Musée du Quai Branly (France), Musée d’Art et d’Archéologie (Madagascar), Barnes Foundation (USA), the British Museum (UK), Israel Museum (Tel Aviv)26. The largest collection is today at the Musée du Quai Branly (MQB): 51 pieces, which include 25 objects and 26 rubbings. It inherited these works from two earlier museums, the former Musée de l’Homme and Musée des Arts de l’Afrique et de l’Océanie. Donors include Georges Waterlot, Raymond Decary, Jacques Faublée and Charles Poirier. The conditions under which the pieces (and rubbings) were collected in Imerina, could not be ascertained by the authors, but are crucial for future research.

According to early authors, the carved Merina bed panel formed the lateral (western) side of the bed that faced the room; the second (eastern) lateral side (being pushed against the wall) was left uncarved. But if our supposition is correct, that the bed was integrated into the wall structure of the northeast corner (at least in some cases) then the bed required only two panels (western and southern), the other two sides (northern and eastern) being made by the house walls. In either case, only the one board was carved. It was made from a hardwood, from pallisandre, rosewood or ebony. A study of extant examples shows that bedboards take the form of a long flat plank, about 170 cm long x 20 x 4 cm wide with a depth of 4 to X cm (Fig. 1). A small subset have less width and greater depth, measuring ca. 180 x 12 x 7 cm. The two ends of the boards, or their sides, often include a device (a hole, slot, groove or tab) to join the piece to the other board(s) making up the bed. The heavy patina and wear of most boards indicate they were not produced for colonial fairs or the European market27.

Figure 1: Overview of a figurative bedboard (from Boudry 1933 plate VII)

The design of extant Merina bedboards generally follow a standard design. The four edges of the board are lined with one or more rows of interlocking shapes, such as fretwork, arabesques or scrolling vine-like forms. Often large carved concentric squares embellish the two far ends and center, with the remainder of the space given over to other, large motifs. These motifs can be grouped into three broad categories: 1- the purely geometric, 2- the textual, 3- the figurative.

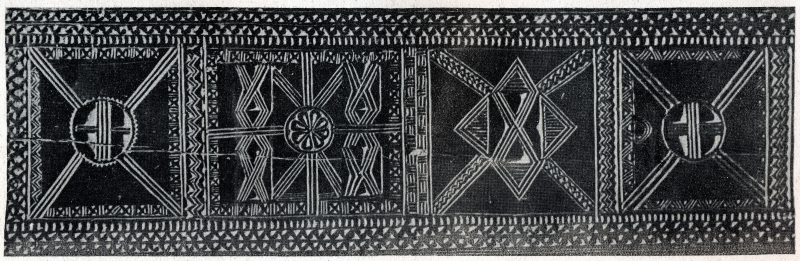

A small number of extant boards employ only geometric motifs at their center (Fig. 2). The most frequent is a large X shape alternated with other forms, such as stacked lines or rosaces (very occasionally, small human forms). These same shapes are commonly found in woodcarving throughout the island, and in other arts, notably beadwork and textiles. In some instances, such as MQB 71.1946.43.1, the motifs are deeply incised.

Figure 2: Detail of a bedboard with geometric motifs (from Boudry 1933 plate VI)

A single existing board features textual script. Piece MQB 71.1990.57.1049 spells out “Rasoaherina, reine de Madagascar” [original in French]. However, there is some doubt that this in fact a bedboard, as its back is also carved (with large lozenges), and it lacks the holes, grooves or tabs to join it to other boards.

The great majority of extant bedboards belong to a third category: figurative scenes of zoo - and anthropo-morphic forms. Whether this style was the most produced, or simply that most preferred by European collectors, remains unknown.

Two distinct carving styles can be identified:

1 incised outlines (Fig. 3). The perspective tends to be “naïve,” the figures presented frontally and floating freely in space.

Figure 3: Detail of a bedboard of the incised outline carving style (from Boudry 1933 plate VI)

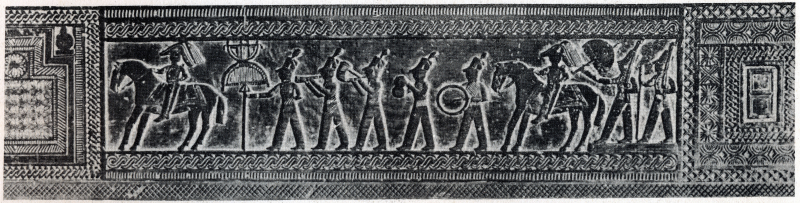

2 bas-relief carvings (Fig. 4). Figures are typically placed on one plane and in profile. The carving is oftentimes extremely accomplished so as to indicate the hand of a professional.

Writings and actual pieces show that some of these bas-relief carvings (e.g. Barnes Foundation a108) had their cavities filled with white clay (kaolin), which had the effect of setting off the dark wood of the upraised figures.

A study of known illustrations and museum examples reveals a set of common motifs to both carving styles:

• one or two men (ostensibly officers) mounted on horses and wearing two-cornered hats.

• a row of military musicians in tall hats playing wind instruments and drums, sometimes with a standard bearer.

• a row of marching soldiers carrying bayonets, preceded or followed by several men (ostensibly officers) in two-cornered hats holding sabers, staffs or guns.

• a row of kneeling soldiers pointing bayonets, or firing a canon.

Figure 4: The left and rights sides of a bedboard of the bas relief carving style (from Boudry 1933 plate VIII)

In all the foregoing scenes, the men are dressed in European-style military uniforms.

• a group of three or four women facing frontally. Several women in dresses and tufted hairstyles hold an umbrella or child in one hand, square objects in the other; several women, who appear to be servants, carry loads (probably water jars) on their heads.

• a crouching man milking a cow; a second man may restrain a calf nearby.

• rows of guinea fowl; other domestic fowls that can be confidently identified as turkeys, chickens and ducks/geese.

• frontal view of a house or houses with crossed gable beams, or several conjoined house fronts which in some instances may represent palaces (Radama’s “country” palace Soanierana?).

• one or two figures seated in high backed chair(s). Often it is an officer in a two-cornered hat, but may also be a man playing a zither (valiha), or a woman seated with a square object on her lap.

• two confronted bulls.

Other, less frequently occurring, figures include men bearing a palanquin, men with spears or wrestling, women pounding rice, soldiers firing canons, rosaces, lone or paired animals such as dogs, crocodiles, and goats. Plants and leaves (popular in contemporaneous Merina stone tomb carving and brocaded textiles) are rarely depicted, but appear in glorious detail in MQB 71.1934.106.42-43.

Individual figures and scenes may be arranged continuously or placed in discrete cartouches. Typical is Fontoynont’s plate 8, shown here in Fig. 4. At each of the two ends is a cartouche filled with concentric squares; at the center is a cartouche containing a square (filled with petal-like shapes) with circular forms on top. On the right half of the board is a military band of drums and horns; flanking the band are figures mounted on horses in officers’ dress and two-cornered hats and two-foot soldiers in peaked hats, carrying bayonets, with one holding an umbrella over the officer. The left half of the board depicts 1- a crouching man milking a cow, its young calf nearby, 2- two ladies wearing striped dresses, one holding an umbrella and carrying a square shape in her hand28 the other holding the hand of a child; a shorter women (ostensibly a servant) carries a water jar and holds an umbrella over this women, 3- two marching military officers in two-cornered hats and fitted and striped waistcoats who carry erect sabers, 4- two bulls confront one another, their horns locked. The carver has sensitively captured movement and space, the incessant march, the muscled standoff of the bulls, and the clashing of cymbals. Only the horses appear somewhat awkward in look and gait, perhaps due to their rarity in Imerina.

Origins, influences, meanings of figurative bedboards: conservative assessments

What do these scenes represent, why were they chosen, when were they made and what was their significance? These questions are not easily answered. Between 1923 and 1931 Camo, Camboué, Waterlot and Fontoynont confidently put forward several theses that have been repeated (and elaborated) in publications thereafter. If unable to offer novel answers to questions of origins, influences and significance, we nonetheless hope to provide a service in re-examining some of these earlier interpretations, in cautioning prudence, and in suggesting some lines for future research on Merina carved bedboards.

The inability to date museum pieces and the lack of contemporary historic commentary (which reveals practically nothing on who made or used bedboards) prohibits any certainty in dating the origins of carved bedboards or tracing stylistic change. A plaque affixed to a piece in the Barnes Foundation attributes it to the eighteenth-century. But this is most certainly erroneous. The few firsthand descriptions of late eighteenth-century Imerina make no mention of figurative bed panels. Indeed, a French witness to the opening of royal tombs in 1897 pointedly complained that only geometric ornamentation was to be found on objects in the earliest tombs, including the wooden throne of King Andrianampoinimerina29. Waterlot30 supposed that the Merina learned woodcarving after subjecting the Sakalava in the 1840s, an untenable assertion as Sakalava-Merina contact was strong and frequent from much earlier; Nativel31, too, ties carved bois de lit to the reign of Ranavalona I (r.1828-1861), but without supporting evidence. Several other authors confidently link figurative bed panels to the reign of Radama I (r.1810-1828). Heidmann presented their life cycle as thus : « Ils commençaient à se répandre sous Radama Ier et obtinrent leur plus grand succès sous Radama II ; puis ils cessèrent de plaire rapidement lorsque l’influence européenne devint profonde »32. We revisit dating and Radama’s likely influence at the end of this essay.

A tenet of Waterlot that needs to be challenged is his evolutionist perspective, which was widely repeated by others and exists to this day in online museum databases33. All authors from Camo onwards asserted that the first bed panels had only geometric motifs (perhaps linked to Arab influence), which gave way over time to ever more naturalistic figures. Lending some support to this argument is Jully’s observation on the lack of figural decoration on objects in early Merina royal tombs (noted above), as well as recent studies on the transformations of motifs on Merina silk textiles that document a move toward realism34. But Waterlot went further by developing an evolutionary scheme for figurative boards: in a first phase, simple forms were done crudely; the second saw a decrease in the size of the central motif; the third phase saw bas-relief carving and more sophisticated imagery; the fourth and fifth saw increasingly skilled carving until finally the central motif disappears and the scenes purely depict a so-called “la vie indigène.” However, Waterlot provided no evidence for his chronology - no justification for dating one board older than another. There is nothing to say that bedboard styles were not coterminous, the products of varying levels of skill or differences in taste. Notably, both the incised outline carving style and the bas-reliefs draw from the same stock set of motifs. Rather than represent evolutionary peak, the accomplished bas-relief carving is much more likely the work of a professional carver or workshop. The design and carving style of the bed panel shown in Fig. 4 (plate 8 in Fontoynont) is nearly identical to two other known examples: plate 4 in Fontoynont and piece A116 in the Barnes Foundation. These three incredibly similar works point to the hand of a single artist. Other groupings could be cited.

An unfortunate tendency in the literature has been the hasty identification of events, people, animals, and even plants. As typical examples, Fontoynont declares the central figure of one piece to be King Andrianampoinimerina, while Charles Poirier asserted that others show Ranavalona Ist, the prime minister or “exercices d’équitation à l’école de cavalerie du Palais royal”35. Yet these authors do not justify their specific identifications. There is nothing to indicate that these figures (who appear repeatedly on boards in various guises and combinations) do not depict generic court life and military processions. Another careless practice is to classify certain motifs (e.g. cattle and fowl) as representing “la vie indigène” and oppose them to figures of “European influence” (e.g. horses and figures dressed in European-style clothing). Boudry36 typically dismissed the latter as “puerile imitations of European fashions”. All of the scenes and figures, however, are arguably local; they depict (urban) Merina society of the mid-nineteenth-century: by that time, European dress (both military and civilian), arms, and musical instruments were entrenched features of local life. The horse, too, had been assimilated as an honorific animal; on Betsileo cenotaphs (teza) the image of a horse and rider was sometimes carved on the prestigious top portion where alternatively a bull might be portrayed37.

What we feel to be a safe conjecture, given the current limited state of our knowledge, is that the figurative motifs globally embody signs of wealth, high status, and force in Imerina of the second and third quarters of the 19th century. The music and dance, men wrestling or brandishing weapons, crocodiles, fighting bulls, and women carrying water, pounding rice or tending children, are all (gendered) signs of energy and force, common tropes in Malagasy funerary art. The livestock, dress, accessories, arms, servants, chairs, filanjana, crossed gable beams, etc., meanwhile, all represent primary signs of wealth and elite standing. In this regard, further research is needed, but it may be that one of the most common motifs of Merina bed panels (thus far entirely ignored by scholars) represents the nineteenth-century fashionable Merina tomb: it is the square form which is set in a cartouche at the center (and/or ends) of many boards; covered with petal-like forms and topped by a half medallion and what appear to be two large round water jars, it is strikingly similar to the new style of stone tomb (immense, ornate, carved with vegetal motifs) that likewise appeared in Imerina in the first half of the nineteenth-century.

One interpretation withstanding scrutiny is the thesis by Fontoynont that the wall paintings (“frescoes”) in Radama’s royal palace Tranovola (“Silver House”) served as the stylistic influence for several key scenes in figurative bois de lit: the military figures and group of frontal women. Radama commissioned a Creole carpenter from Mauritius named Legros to build Tranovola. It was the first building in the palace complex to have two stories, a verandah, and glass windows. Important to our story, the walls of its main room were covered with “frescoes.” According to Fontoynont, they were created in 1822 by André Copalle, a Creole artist from Mauritius38. The paintings were divided into three horizontal bands, with vegetation and geometric figures at the top and bottom, and scenes of humans in the middle (Fig. 5). The last include military processions, circumcision events, and women dressed in tailored dresses. The fashion for painting interior house walls with figurative scenes appears to have spread. In the 1860s Sibree39 observed that the

large country-house belonging to the present secretary of state is a continuous line of figures around the walls, in the gallery of the chief room. These paintings represent a variety of characters and classes – military, judicial, agricultural, etc. ; they are about a foot or a little more in height, and are very rude in drawing and colouring.

It is certainly the case that the themes and conventions of the Tranovola wall décor are to be found in the majority of figurative bois de lit: military band processions in profile, mounted officers, canons, women portrayed frontally with a very distinctive round, puffed hair style40.

Figure 5: Scenes painted in the main salon of Radama’s palace Tranovola (from Boudry 1933 plate XI)

This returns us to the tricky issue of dating the boards. Whether or not figurative bed panels emerged during Radama’s reign (1810-1828) cannot for the moment be positively determined. However, Radama did introduce to Imerina major innovations that likely influenced their making, iconography and fashionability. From 1818 he famously welcomed British and Mauritian artisans, including several carpenters41. By 1826, one of these men, James Cameron, had introduced the saw and lathe and was overseeing 600 Merina apprentices42. Merina craftsmen reportedly made most of the wooden furniture that furnished royal palaces. Radama adopted European dress for himself and court so that within a decade elite Merina men and women were dressing in tailored clothing. He imposed European-style uniforms and accessories (hats, sabers…) on his standing army, introduced horses and a military band playing European tunes and instruments (sending his musicians to Mauritius for training). As importantly, he lifted certain sumptuary laws and noble privileges such as traveling in palanquin (filanjana), which just may have included the use of the bed.

Radama’s innovations forever shaped Merina material culture. Under his influence, ornamentation and style, in addition to cosmological spatial considerations, came to speak value and status in houses and furnishing. He decorated his Tranovola with sculptures, curtains, mirrors, paintings, wallpaper, clocks, tables, chairs and sofas, interior fashions which quickly spread to high society. In elite homes, into the 1840s, the bed remained positioned in the main salon, although it now competed with chairs, tables and cabinets43. But this was soon to change. Radama himself had adopted and encouraged the creation of a separate sleeping room. By the 1850s, missionaries were cheered to observe that owners of the “better class of dwellings” were screening off the sleeping corner with a curtain or constructing a separate sleeping room altogether44. The bed was no longer a visual focal point of the main room and, perhaps not surprisingly, the vogue for carved bedboards eventually faded, so that by 1923, they were already scarce for European collectors.

Conclusion: hybrid objects

A product of its times, the early literature on Merina carved bed panels was ambiguous, both praising the artform as original and accomplished, but also maligning it as inauthentic, even a sign of degeneracy in Malagasy art, a result of ill-defined “imitation” and “European influence.” However, it is these very “hybrid” arts that are today attracting scholars; they reveal the longstanding and ongoing connections between peoples, as well as artists’ longstanding ability (and eagerness) to explore new methods, materials and subject matter. Today’s scholarship on “entangled objects” views hybrid works through the lenses of appropriation, cultural authentication, and subversion on the parts of artists and patrons. In the instance of Merina bed panels, certain artistic conventions, tools, and possibly the training, may have originated with Europeans. But they were appropriated by local artists to depict wholly local scenes of (urban) Merina life of the nineteenth-century, and applied to an object of supreme significance in nineteenth-century Malagasy culture, the bed. The West’s ongoing preference for what it deems “primitivist” art should not preclude the bedboards’ being (again) recognized as a unique artform meriting display and study.